Editor’s note:

This piece about the current crop of art shows in Paris was submitted to us days before the latest round of carnage in the City of Light. The recent attacks certainly overshadow the offerings at any of these exhibitions, but as you’ll see below, some of the materials on display directly address the social and political questions highlighted by the conflict with global terror. Our correspondent, Paris-based artist Matthew Rose, focused his inquiry on wars past and present, as addressed in several different shows. This is an instance of a piece being at once prescient and dated; we offer it here as a work of commentary, but also as a reflection of the immediate, intrinsic ties between art and the world it seeks to represent.

Some years ago I wrote a piece for The Journal of Art called “Art During Wartime.” The war at that time was George H.W. Bush’s 1990 Gulf War—Desert Storm”—and it was principally about oil and nominally about freeing Kuwait from Saddam Hussein’s takeover of the tiny oil rich kingdom. The art featured in the article included Ron English’s New York billboard Guernica, a copy of Picasso’s masterpiece about the bombing of that Spanish town in 1937 by Hitler’s Luftwaffer at the behest of dictator Francisco Franco. English, though, added a Bushism from his war speech across the painting: “New World Order.”

A Papo Colo installation of a roomful of sand at New York’s Exit Art was also cited, along with a dozen other works sprinkled about downtown New York galleries and a number of red (blood) screeds, violent videos running in loops, hundreds of plastic toy soldiers, photographs of previous wars, camouflage uniforms and paintings, and the mandatory wooden guns. Clearly the art world heaving against war did little to end that one, or prevent new ones. Wars end when the economic interest wanes or is destroyed.

Since World War 2—the good war—the world has lumbered from one conflict to another, destroying lives, villages, the earth and spreading misery, all in the employ of some notion of liberty, democracy, freedom and peace. Bombs rain down, people are slaughtered, and the corporations try to grow new markets from the ashes. We close our eyes and down gin and tonics, toasting the openings of the anti-establishment art world, the beating heart and consciousness of our era. But we all know it’s mostly bullshit— that art is less about changing hearts and minds than it is about getting ahead, breaking auction prices, finding purity in color or form and getting paid for it.

Americans protesting with paintings and sculptures against far away wars (or even riots in our cities) seems in fact, noble; other artists in other countries doing the same permits some context and perhaps relevant news—like Ukrainian artists last week turning statues of Lenin into WIFI hotspots featuring Darth Vader. But it’s terribly hard to change hearts and minds with titanium white or twisted metal, and things really don’t change that much in living rooms anywhere unless you tear down the house, or at least do a total paint job. And even then, moving the furniture about is fairly useless.

But the art-critical protest march continues unabated with fluctuations in loudness, variations in shock content and uneven bursts of cleverness. War art in the end, is not terribly interesting and obviously not much of a contender in the auction rooms. Case in point: The global orgy of art in Paris this past week. Following the merry circus of money at Frieze in London, Paris’ contribution to critical thinking about wars launched decades ago, and (still) ongoing, was at most mild in the peace and love department; the focus in the French capital was more on investment and interior design than the Syrian refugee crisis, the attacks on black churches in the American south, or the nonstop anarchism expressing itself in practically every backwater under the guise of anything and everything religious. But there were some rumblings.

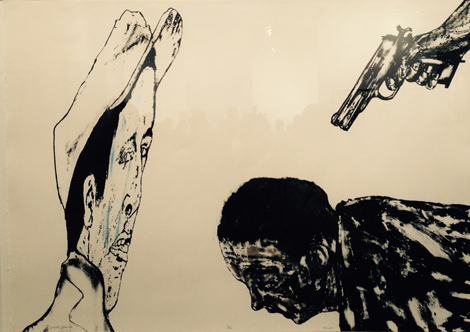

At the Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain (FIAC), this fall’s main Paris venue held in the ever-gorgeous Grand Palais—one gallery, London’s Hauser & Wirth devoted its entire space to war and conflict, terrorism and global chaos. Curated by Paul Schimmel of LA/MOCA, and the new head for Hauser Wirth & Schimmel’s soon-to-be opened gallery in Los Angeles, one was reminded (in this space at least) that we are living in dangerous times. Leon Golub’s portraits of Kissinger and other political criminals (according to some), and a dramatic black-and-white print of an execution—White Squad, 1967, were spot on. Schimmel also featured a pair of text/painted works by Philippe Vandenberg, including KILL THEM ALL, 2008, a scrawl on wood that emanates from a frenetic hand, a piece of protest drama. Where to put it, though?

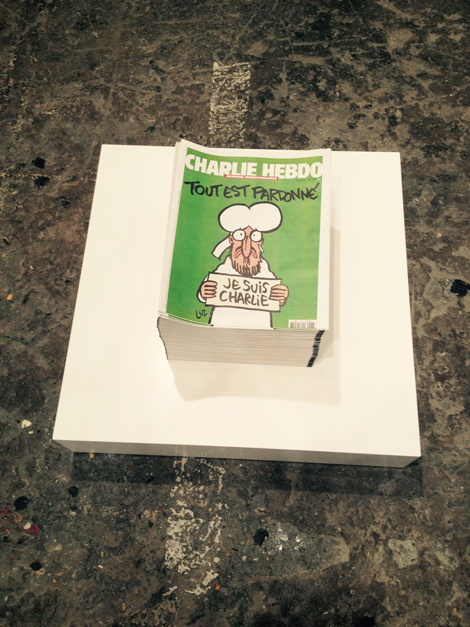

In a nod to the tragic killings of the staff cartoonists at the French satirical weekly a year ago, Schimmel also stacked a 100 copies of Charlie Hebdo on the floor as a kind of temporary sculpture. No, visitors were not encouraged to take a copy; it was a gesture that was decidedly not for sale, and served as a reminder and memorial to the slain artists from the city where the killings occurred. People noticed. But, then? Yes, politics demands we act. But art?

On the same stand was a goofy (but effective) video of America We Stand As One, a 2005 work by gadfly and art world clown-genius, Christoph Büchel. The Swiss-German filmed a singer in a 1970s shag hair style sporting a USA T-shirt crooning out the song against the backdrop of a blue ocean, waves crashing all around him, the lyrics translated into Arabic.

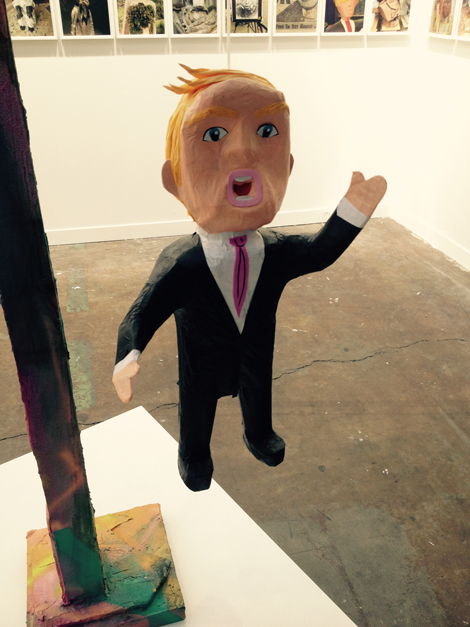

Politics took a fun turn nearby, however, with the one-work installation by Rachel Harrison at Greene Naftali’s stand. Harrison’s one person show, a multi-panel photographic journal of statues, cardboard prints, manikins of Indians, Elvis, Napoleon, Michael Jackson (by way of Jeff Koons) and others. Fronting that display was what seemed to catch everyone’s eye—was GOP-leading presidential hopeful, real estate billionaire Donald Trump as a Mexican piñata, hanging from a pole, his mouth lined pink as if he were a blow up sex toy (perhaps he is). Yes, people did indeed recognize The Donald; and while not specifically about war and peace it was clearly about Trump’s war on Mexican immigration (“Build a wall!”).

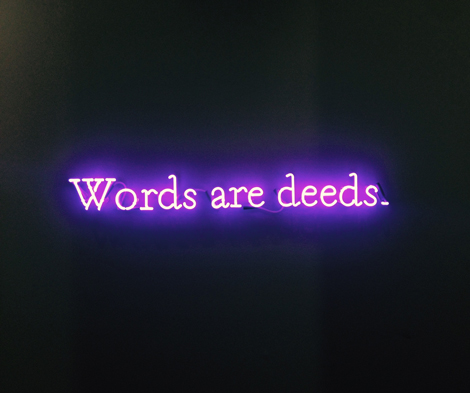

Joseph Kosuth—always a reliable neon scribbler, gets us to see what we need to see. The language-obsessed artist quoted Wittgenstein to produce a self-reflexive text work: Words are deeds, 1991. Plugged in at Paris’s Galerie 1900–2000, the piece shines a light on the Austrian language philosopher’s clearest iteration of diplomacy, even if his intent was more about speech as action, And perhaps riffs off of the Book of Genesis —“In the beginning was the word…”

At the YIA fair across town at the Carré du Temple, Adi Brande’s untitled 2013 work, made some kind of token acknowledgement to the violence in the Mid-East and perhaps in Israel itself. His inkjet print of a prayer rug sliced up and married to a sliced up pistol, dared to invite conversation, but was perhaps too static and unattractive to get the sort of reaction the artist was fishing for. The work was featured amid other pieces from Israeli artists at Tel Aviv’s Cohen & Schwartz.

While not specifically about war or refugees or Mexican immigration or political crimes against humanity, Sean Landers Maroon Bells (Deer), 2015, seemed to sum up this years’ art-and-war material. His 10-point buck, portrayed in 2 x 1.5 meter oil-on-linen canvas at Berlin’s Capitain Petzel gallery, poses majestically along the shore of a lake. The deer is framed by two green mountains and stares us down. But what we admire here is the buck’s coat—a hunting man’s woven wool plaid. The title is born of the twin peaks just outside of Aspen, Colorado, an idyllic nest, a paradise on earth. Nothing bad ever happens there.

Matthew Rose is an artist and writer based in Paris, France. Instagram: @mistahcoughdrop